Grief and Loss

Grief is a normal and natural response to loss.

We tend to associate grief with death. For many, the loss of a loved one is one of life’s most painful experiences. It can impact every part of our lives.

We also grieve nondeath losses. Many life events can trigger grief - the end of a relationship, a major illness, injury, job loss, financial hardship, or any significant life change. Nondeath losses can be uniquely painful and may be accompanied by complex emotional responses.

If you find that time has not healed your wounds and that you need additional support, I am here to listen and companion with you as you process the emotions, thoughts, and changes that the loss brings.

What is grief?

Grief is the day-to-day experiencing of loss. That includes your feelings, your thoughts and how you get through the day/night.

There is no timeline for grieving. Your grief may be relatively brief. Or you may find that you grieve, in some form, for the rest of your life.

Grief is unique to the individual. You may be surprised or confused by your reaction to loss. Grief is affected by coping style, comfort with emotions, personality, situational factors, and relationship with the deceased. It is common to experience a need to cry, laugh, or run away. Your emotions may ebb and flow. You may oscillate between confronting the loss and avoiding it. You may need quiet and solitude. You may grieve as you stay busy. Or you may find that you feel nothing.

Grief is unique to the individual and because of this you may feel isolated in your grief. And our grief-averse culture can leave you feeling alone.

Grief will impact you in many ways. Grief and loss will change you. You may find that you have new priorities. You may also notice a new sensitivity to the loss of others. Or you may even find that you question your beliefs. Some people question the meaning of life after a significant loss.

There are no stages .

Elizabeth Kubler-Ross first published her book in 1969 describing the five stages of death and dying. In the 50+ years since that time; however, grief researchers have not found evidence to support her stage theory.

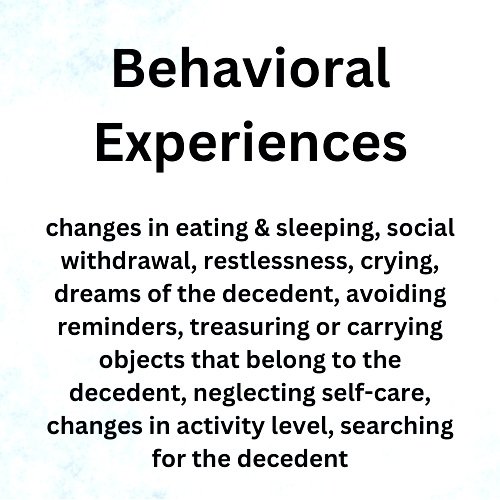

What they have discovered is that grief is a complex neurobiological process that affects the griever emotionally, physically, behaviorally, and cognitively. Grief impacts nearly every area of a person’s life in a unique combination of way.

No matter how long it's been, there are times when it suddenly becomes harder to breathe.

Heart-Centered Psychotherapy for

~ Child Loss

~ Spouse / Partner Loss

~ Parent Loss

~ Sibling Loss

~ Loss by suicide

Want to learn more about grief?

Scroll through these articles and see what catches your attention.

-

The Neurobiology of Grief.

Our brains undergo some profound changes after a devastating loss. Your brain has a painful problem to solve. When your loved one was alive, your brain created a special kind of map for that person. And a lot of time and energy was used to create this map. It really struggles to navigate the new reality of loss and transform the relationship.

According to Mary-Frances O’Connor (2022) a neuroscientist and grief researcher at UCLA, we live in two worlds after a significant loss. She writes, “One world is a virtual reality map made up entirely in your head.” The example she offers is one in which you can navigate your home in the darkness of night because your brain has created a virtual map of your home in your head. We use the mental map to navigate the “real” world. This map is stored in your hippocampus.

Which brings us back to the problem that your brain must solve. The mental map no longer matches up with reality. When your loved one dies, they no longer exist in same dimensions that you used to create the map – time (now), space (here), and attachment (close). It might be helpful to think of these dimensions from the viewpoint of an infant. A securely attached infant learns that his caregiver will return when he cries out. There is security in knowing that she physically exists somewhere in time and space – even if he cannot see her. The dimension of “close” is the knowledge that he can depend on her for comfort and safety when needed. In this way, the infant creates a mental map of his caregiver that exists in dimensions of time, space, and attachment.

Because our brains have a hard time reconciling a new reality with our mental maps, we search for your loved ones. It is not uncommon for grievers to hold on to (even just to smell or touch) things that belonged to your loved one. We need to feel close to them. Often people turn to religion or spiritual practices to soothe the pain with the hope of reconnecting and bridging dimensions of time, space, and attachment. Religious rituals help us cope with our biological and psychological yearning to connect. And it is this VERY STRONG YEARNING that is at the heart of grief itself. An infant simply cannot survive in the world without his caregiver.

Our brains are also good at making predictions and filling in gaps when we lack information. As an example, let’s say that your deceased spouse got up every morning at 6:00 and started a pot of coffee. At 6:00 your brain still expects this to happen. When it doesn’t you are forced to take in and process two experiences that do not match up. Your predictive, map-creating brain is out of sync with your new reality. This discrepancy, which is sometimes out of our conscious awareness, causes a wave of grief.

The process of altering your mental map or predictions takes a long time. Your brain has learned not to make changes based on a singular incident or occurrence. It needs proof over time. With each wave of grief, your brain takes note and begins to slowly (very slowly – day after day, month after month, or year after year) create a new mental map with new predictions. This happens when you find yourself wanting to call or text your deceased spouse, share some special news, or plan an outing without your loved one. You can be waiting in the drive through line and suddenly remember that you only need to order food for one now. In those countless ordinary moments, your brain is slowly changing itself to adjust to a new reality.

Reference

O’Connor, M. (2022). The Grieving Brain: The Surprising Science of How We Learn from Loss and Love.

-

Grief has its own timeline.

One cool spring desert day, way back in my adolescence, I sat with my grandmother. The best word I can use to describe her is stoic. She rarely showed emotion. Nanny had a tough exterior and kept people at arm’s length. She grew up on a farm in Texas and moved to California as a young woman during the Dust Bowl. She and her family worked the fields. For many years, they lived in a tent and picked fruit, vegetables, and cotton up and down the Central Valley. It was a hard life. They were often hungry and not sure where their next meal would come from.

But on that day as I sat with her, I noticed a portrait of a little boy - maybe two or three years old. It was hung a little too high and surrounded by the blank starkness of an otherwise empty wall. Many decades had passed since she buried her sweet baby boy. When I asked about him, her body collapsed. A wave of grief overtook her. She had no words. Not knowing what to say, I sat in silence as she sobbed. The pain of the loss seemed to inhabit every cell of her body. When her voice returned - shaking and unsteady - she shared the story of his passing. She talked about holding and rocking him in her arms as he took his last breath.

Now, as a grieving mother myself, I share an unfortunate and heartbreaking kinship with my grandmother. I am a member of a club that no one wants to be part of. The lesson I learned that day is that waves of grief – the kind that overwhelm you and seem to take over your entire body – can happen decades after a devastating loss.

A wave of grief can hit at the mention of your child’s name. It can hit at the grocery store when you see your son’s favorite food. It can hit during random everyday moments, without any warning. My family remembers one such moment. While we were talking down a dirt road toward a small farmhouse on a sweltering Texas summer evening, a tsunami-sized wave of grief hit me. My legs could no longer support me. And my family helplessly watched as I stumbled and screamed at the top of my lungs, begging for death to reunite me with my son.

I’ve learned that these waves of grief are a normal and natural response to loss. When someone you love dearly dies, you may experience these waves in varying degrees of intensity for the rest of your life. Your relationship with the waves, however, will most likely change. In the beginning, it feels like you won’t survive. You might even hope that you don’t survive as the yearning to be with your child seems to rise up from the core of your being. As time passes, the painful pangs of grief may become more familiar. You learn ways to exist with the kind of heartbreak that most parents never want to imagine.

If you join a child-loss support group, you will most likely hear parents say that time has not healed their wounds. Sometimes 10, 20, even 30 years after the loss. Something deep inside their being continues to cry out for one more hug, one more conversation… just a few more precious moments with their child.

When grief expert David Kessler is asked how long grief will last, he often responds with another question, “How long will you love them?”, indicating that there is no time limit. You will move through your grief in your own time and at your own pace.

I know that I will love my son for the rest of my life. But I do not have the advantage of looking back 10, 20, or 30 years to know how my grief will change over time. Instead, my grandmother, mother-in-law, and many other brave souls, are my guides – gently illuminating the dark and uncertain path ahead with their shared wisdom and lived experiences of child loss.

-

Grief & Yearning

Many people that are grieving experience deep yearning. In its most basic definition, yearning can be thought of as a grief response in which one strongly desires to be the person that is deceased. An example is a bereaved daughter eating at a restaurant. She tastes something that reminds her of her mother. Quite naturally, she yearns for her mother – to be close to her, to share this experience with her… just to be in her loving presence again.

The experience of yearning in grief is especially prevalent in close relationships like those we have with our spouses, children, parents, and siblings. And, it is processed differently in the brain than the yearning we experience after a relationship break up or other non-death losses. Some grieving mothers describe the experience after losing a child as “living in two worlds”. They may say that part of them died with their child. Or they may say that it feels as if part of them is in the spirit world with their deceased child and the other part is living in the physical world. Whatever your spiritual beliefs, the desire to protect and care for one’s child does not end when they grow up. And it certainly does not end with your child’s death. If you have lost a child, then you most likely understand the experience of yearning to be with your child.

People respond to yearning in MANY different ways. You may find that you engage in different responses, depending on the situation. A few of the most common are:

Avoidance. We simply avoid things that remind them of us of our loved one. When we experience yearning, we immediately do something to refocus our attention and energy.

Shift Your Emotional State. Instead of avoiding things that remind us of our loved one, we may choose to refocus on a memory of our loved one that brings comfort (and even joy). We recall a favorite memory as a way of shifting our internal experience. This can be difficult to do for many of us, especially in the first year or two after a tragic or significant loss.

Engage the Yearning. A third response is to allow ourselves to sink into the feeling of yearning. Sometimes when we allow ourselves to really engage with the pain, we may notice that we begin reliving details of our loved one’s passing or get caught up in all the what-ifs. Our minds may go in many different directions when you allow the yearning. This is normal. Our minds are trying to make sense of our new reality.

Yearning is part of the grieving process for many people. And it is adaptive to move between each of these responses. The response that you choose will depend on a variety of factors, including your surroundings and situation. As an example, it might be appropriate to engage in avoidance when you are at work and need to meet a critical deadline. However, an over reliance on avoidance can also contribute to prolonged grief.

Do you have a preferred way of responding to your yearning?

Note: It is important to distinguish between yearning and having an urge to die. If you are thinking about suicide, please reach out to someone. The amount of pain that you are in might feel overwhelming, but your life still matters. It matters more than you may realize in this moment.

Suicide and Crisis Lifeline: Text or call 988. Help is available.

-

Do you find yourself expecting your loved one to walk through the door?

This is a common experience. And current research suggests that there may be evolutionary neurobiological processes at work that create this phenomenon. Think about all the information about your loved one that has been permanently coded and stored in your brain and body – their smile, their routines, their smell, the tilt of their head, their humor, their warmth, their favorite food, the sound of their voice, and ALL THE MEMORIES you shared.

Then they are gone.

But all that information is still there, creating a mismatch between all that you know and your current experience. Joan Didion (2005) writes about this type of thinking in her book, “The Year of Magical Thinking”. Didion talks about not wanting to get rid of her husband’s shoes, just in case he needs them. She is not delusional. She knows that her husband is no longer living. Yet there is a part of her that expects him to walk through the door.

It takes time for your neurobiology to sync up with your new reality.

And it’s not just humans that need time to process and integrate loss. O’Connor (2022) shares stories of mother chimpanzees who carry their deceased infants for days, weeks, and even months after they pass. They will groom their sweet lifeless babies and loving care for them. Some chimpanzee mothers stop grooming themselves – a sign that they know their baby is deceased and that they are in mourning. Other members of the chimp community seem to know this as well and may take turns grooming the bereaved mother in a show of compassion while she cares for her baby. Eventually, the bereaved mothers will let go of their deceased infants. However, if the deceased infant is removed from the mother before she is ready, she will search endlessly for her child. She hasn’t been given enough time to integrate the loss.

One of the most compassionate things we can do for the bereaved is to give them the space, time, and support needed to integrate the loss, with the understanding that what they are experiencing is a normal and natural response to loss (regardless of how long it lasts). We are wired to believe that our loved one is not gone. They are caught between knowing that their loved ones are gone and still living with neurobiological processes that predict and expect their loved ones to return.

If you are grieving, be gentle with yourself. Take all the time you need.

-

Would you like to strengthen your connection with your deceased loved one?

You might be interested to know that there is a specific EMDR protocol that honors continuing bonds after death while decreasing the distress that accompanies grief. It is especially helpful for those that have experienced a traumatic loss. IADC is a brief psychotherapeutic intervention that can be done in two treatment sessions, typically 90-minutes each. However, it is often more helpful to integrate this protocol into more comprehensive therapy that addresses the many layers of grief.

IADC (Induced After Death Communication) is an EMDR protocol. It is unlike traditional talk or grief counseling. The IADC protocol feels much more experiential and spontaneous. When the grief-related distress diminishes, clients generally experience a state of calmness, openness, and receptivity. In this state of calmness, up to 75% of clients describe feeling a deeper connection with their loved one. Some describe a general feeling of love, joy, or peace. Others report sensory experiences (sights, sounds, tastes that they associate with their loved one). It is also common for clients to say that they feel the “presence” of their loved one. Much like EMDR, in general, your experience will be unique to you and guided by your internal wisdom.

But is it real or in your head? In truth, it does not matter from a therapeutic standpoint. My role is to administer a grief protocol that sets the stage for a healing experience aligned with your own natural way of grieving and belief system. Some people do believe that they are connecting to their loved one “on the other side”. Others see it as a therapeutic tool in which the nervous system experiences catharsis brought about by the release of distressing emotion and desensitization of traumatic memories. Most do agree, however, on the authenticity of the experience and its healing effects.

Will the waves of grief stop? Maybe. It really depends on your situation and your relationship with the deceased. Many clients report improvement in grief-related symptoms. For them, the waves of grief may subside or be much less intense. But I cannot say that this is true of all losses. Having lost a child, I cannot imagine a time in my life without waves of grief. For me, personally, it created a small opening that allowed joy and peace to peek through, providing me with moments of respite from the sadness – moments where I was able to connect to the love that still lives in my heart for my son.

If you are interested in learning more about this unique form of therapy, there are a few resources that are helpful.

Dr. Bodkin’s book, Induced After Death Communication: A Miracle Therapy for Grief and Loss, is a great place to start.

Life with Ghosts, is a documentary that chronicles one woman’s grief experience, as well as the research on IADC conducted at the University of North Texas, and

The Center for Grief and Traumatic Loss website provides resources and information about ongoing research.

If this is something that interests you, schedule a free consultation so that we can chat.

-

Frozen Grief: Ambiguous Loss

Ambiguous loss is unique and different from other types of losses because it is steeped in uncertainty. This uncertainty can impact one’s identity and relationships. People crave clarity but often find little. For this reason, it can be one of the most difficult losses that people experience. Pauline Boss (1999) describes ambiguous loss as frozen grief. She writes, “ambiguous loss can freeze people in place so that they can’t move on with their lives.”

One of the hardest things about living with ambiguous loss is that your experience is rarely, if ever, validated. Other people may not even see it as a loss. Some examples of ambiguous loss are:

Examples of Ambiguous Loss

Your loved one is physically absent but present in your heart and mind. Two examples are:

Military Families. Your loved one is away on military assignment. This can be an especially difficult time for many military families although few people outside of the military community are aware of the sacrifices made by military members and their families.

Incarceration. Another example is a loved one that is incarcerated. The removal of a loved one from day-to-day family life can be very challenging. Sometimes, family members are afraid to even acknowledge that they miss their loved one because of the immense stigma around incarceration.

Your loved one is physically present but changed in profound ways, such as severe brain injury, addiction, or severe mental illness. “When the loss is the result of a disability or illness, even strong families need help managing the stress,”(Boss, 1999). Few things can impact us like a loved one’s addiction or severe mental illness. It’s common to see high levels of anxiety within the family. They will often say that they do not feel like a “normal” family indicating that there is little understanding within society regarding the impact of these situations on their lives.

Your loved one is physically present and there is a shift or transition (i.e. religious conversion and gender identity). Research suggests that some family members experience ambiguous loss and grief in reaction to these types of changes. In the case of religious conversion or deconstruction, there may be a fear about their loved one’s eternal fate. Along those same lines, some may worry about the future of their transgender family member. And it is also important to recognize that this can be a profoundly difficult time in your loved one’s life, as well:

Religious Conversion or Deconstruction. When one begins to deconstruct a set of religious beliefs, they may lose an entire network of support, connection, and community. It is common to feel isolated and alone.

Gender Transition. Transgender persons can experience the same loss of community and support, but with the additional burden of having to navigate a rejecting, stigmatizing – and sometimes cruel - society.

With an ambiguous loss, there is usually a very real sense of fear, anxiety, and uncertainty about the person’s fate. It is common to feel alone, frozen, or confused - locked inside a painful loss that remains open and unending. Ambiguity and uncertainty seem to deepen the wound.

You may find that you experience many different emotions. It’s important not to compare your experience with that of others. We are all unique. Additionally, it isn’t helpful to minimize your feelings, just because your situation does not include death. Your emotions are valid. Feelings of loss and sadness are an expected response to these types of challenges and changes. If you are struggling, counseling may be helpful.

Reference

Boss, P. (1999). Ambiguous Loss: Learning to Live with Unresolved Grief

-

Disenfranchised Grief

Why do I feel like I don’t have the right to grieve?

There are many reasons for this. But let’s consider two reasons.

First, we live in a culture that doesn’t understand loss and grief. Our grief-averse culture leaves grievers feeling isolated.

Secondly, let’s look at the type of loss. Society doesn’t recognize or validate all forms of grief equally. Some types of grief are not acknowledged or accepted. A few examples of disenfranchised loss include

loss of physical health,

loss of home,

loss of community/culture,

miscarriage,

infertility,

abortion,

estrangement from family,

brain injury,

dementia,

severe mental illness,

addiction,

incarceration, and

loss of faith.

Disenfranchised grief is highly personal. What is painful for one person, family, or community may not be so for another. This may increase feelings of isolation, anger, or shame. It can feel as if your pain is invisible to the world.

What can I do?

Please do not allow others to talk you out of your personal experience. Honor your own way of experiencing and grieving a loss, even when… or rather, especially when society fails to validate your experience.

You may have to actively search for connection and support. Look for support groups with people that have experienced something similar. Many believe that disenfranchised grief is one of the most difficult kind of grief because of the lack of social support and validation - two things that are very helpful in the grieving process.

-

Grief & Holding Space.

Wondering how to support someone that is grieving?

One way you can show your support is by holding space. Your simple presence may be the most healing and helpful thing you have to offer.

Grievers often need someone to be present and bear witness to the pain, tears, and memories. They need someone to hold space for them. When we hold space for another, we show up without judgement. There are many ways to show up for someone (i.e. buying groceries, cooking, housekeeping, taking a walk together, etc.). But one of the most important ways of demonstrating emotional support is by listening – without an agenda or centering on your own experiences. Many people process grief through the sharing of stories. Their loved one has passed, but the memories remain (and may be even more important now). For some grievers, just saying or hearing the deceased person’s name holds great significance and brings comfort in the knowledge that their loved one is not forgotten.

If you are honored with the trusted privilege of holding space for someone, just know that you do not have to fix anything. Your grieving friend does not need fixing. It’s not your job to “make it better” or help your friend “look on the bright side”. It is their pain, not yours. Respecting their emotional autonomy and lived experience is a gift from which you will both benefit. Platitudes (i.e. “God doesn’t give us more than we can handle”) may soothe our own uncomfortable emotions about death and bereavement but may add to the griever’s pain - leaving them feeling discounted, misunderstood, or worse, shamed for a very natural need to share.

The next time you are sitting with a grieving friend:

Take a deep breath.

Notice what emotions come up for you. It’s okay (and may even be healing) to share tears and your personal experiences; however, be mindful of centering on the griever’s experience rather than your own.

Listen.

Be present.

In an ideal world, every griever would have someone holding space for them. Unfortunately, this is not the case. If you are grieving, you may have the added burden of actively seeking out connection and support. And this can be very challenging, especially if you are struggling to get through each day. Further complicating the situation is the fact that not everyone you reach out to will be able to hold space for you. You may be surprised at who shows up and who does not. Just know that their ability to be present is a reflection of their own fears, experiences, and human limitations. Most likely, it has very little to do with you.

One way that you can find solace and connection is by joining a support group that includes peers who have experienced a similar kind of loss. The loss of a child and the loss of a spouse are very different experiences. It might be helpful to connect with people who have “been there” or are going through something similar.

In closing, please remind yourself that grief is the natural response to loss. Be good to yourselves and each other. When we hold space for one another, with grace and compassion, we create a loving place where broken hearts can rest in tender care.

-

Anticipatory Grief.

Grief does not wait until after death when someone is terminally ill. Grief can begin when there is a diagnosis. Grief that happens before death looks like grief that happens after the death. Anticipatory grief does not prevent grief after death. Grief is a normal and natural response to an anticipated death.

As the disease progresses, your suffering may also increase. You may experience feelings of helplessness. You may find it difficult to balance your grief experience and with your need and desire to be present with the person that is dying. You may even feel guilty about grieving because it feels as if you are “giving up hope”.

What does anticipatory grief look and feel like?

Some of the common experiences of anticipatory grief include sadness, irritability, guilt, anger, anxiety, loss of connection, loneliness, insomnia, an urgency to talk things through, rehearsal of the anticipated death, loss of security, loss of role, and feeling as if you are losing a piece of yourself.

How can I prepare myself for my loved one’s death?

You can prepare emotionally for the death by having adequate medical knowledge of the illness/death process, resolving old conflicts, saying “what needs to be said”, and allowing yourself to begin envisioning a life after the death. What if I feel completely overwhelmed?

If you are feeling overwhelmed, it’s a good idea to talk to someone - a friend, family member, pastor, etc. Counseling can also be helpful. Saying goodbye is one of the hardest parts of living. I am here to help you process the changes, new demands, adjustments, and intense feelings that come with saying good-bye to someone you love. I offer you a place to rest your heart and be heard.

-

Ever wondered what the research says about grief and bereavement? As it turns out, the things that we’ve learned from research are interesting Here are just a few of the important findings, from 25 years of grief and bereavement research:

Mourners can experience rapidly changing emotions, especially in the months following a loss. Researchers tracked daily ratings of well-being of mourners following the death of a loved one (Bonanno, 2009). They found a tremendous variation from one day to the next.

People do not grieve in predictable stages. Bereavement is not one-dimensional. Unfortunately, many people keep trying fit grief responses into neat, predictable, stages.

People are hardwired for resilience and recovery (Bonanno, 2009). The graph (see blog for graph) shows three of the most common patterns of grief reactions. Notice the bottom two lines; 85-90% of people have a clear reduction in pain/symptoms within two-years. Now, look at the top line. About 10-15% of people continue to experience high levels of grief/pain at the two-year mark. There are many reasons for this.

My Personal Experiences and the Research

My Father’s Death. Like many others, I did not grieve in predictable stages. There were days, weeks, months that I experienced a wide variety of emotions. If I had recorded my pain on a graph following the loss of my loved one, it might been somewhere between the bottom two lines. But my grief did not start after death and the line would have extended several months prior to the death - when we first learned of the terminal diagnosis. Anyone that has experienced anticipatory grief knows well how painful it is to watch someone you love slowly pass away.

A Nondeath Loss. This loss was devastating (even though there was no death). I was part of the 10-15% that experience prolonged grief. I was in pain for years following this loss - a loss complicated by trauma, ambiguity, and disenfranchisement.

I needed to talk to someone. The problem was finding the right therapist for me. I can still remember the feeling of finally being heard and understood when I sat with my 4th therapist!

I share two of my personal loss experiences as a way of inviting you to be curious about the losses in your life and your own grief. Does your grief response look like the ones in the graph or does it look different? Does the research feel validating or invalidating… or maybe a little bit of both? What are your thoughts?

Reference: Bonanno, G. (2009). The Other Side of Sadness. Basic Books.

-

Grief & Continuing Bonds.

Does the relationship end with the death of a loved one?

Many people have been taught that moving forward after the death of a loved one means severing their connection. However, this idea has been revisited and challenged by grief researchers. As it turns out, some continuing bonds can be healthy and adaptive, while other bonds are not as helpful.

If you have the feeling that the relationship did not end with the death of your loved one, you are not alone. Many people experience the same thing. It is common for some bereaved parents and widows may talk to their deceased loved one. Children that lose a parent may maintain a bond by imaging being watched over by a deceased parent or they may maintain the bond by continuing the parent’s legacy. Some grievers keep an object of the loved one (especially early after a loss). Others write letters to the deceased. Sometimes, visiting places that remind us of our loved one can help us feel connected.

Connections with the deceased can provide solace, comfort, and support as you transition and navigate a life without your loved one. Some of the simplest rituals can create a sense of connection with deceased loved ones:

Wearing a loved one’s favorite color or jewelry on her birthday.

Listening to your loved one’s favorite song.

Setting your holiday table every year with the dishes owned by a loved one as a way of including him//her in your celebration.

You may also discover new or different ways to maintain bonds as you grieve the loss. Early in your loss, you may shy away from activities that you shared with you loved (i.e., dancing, eating at your favorite restaurant, etc.). However, you may discover that these same activities foster connection and well-being later in your grieving.

Difficult feelings do not necessarily mean that the bond is unhealthy. It is okay to feel difficult feelings in connection with your loved one. It’s okay to feel sad. It’s okay to miss them.

Sometimes, however, it may not be helpful to maintain continuing bonds. A relationship that was difficult in life can also be difficult in death. Some questions to ask yourself as you evaluate your continuing bonds are:

Does this bond bring me comfort and connection?

Does this bond support my growth and development?

Is it impacting my life negatively?

Am I able to bring this bond with me as I move forward?

How is this bond serving me now?

And some people do not feel the need to maintain bonds after death. There are many reasons for this. Grief is an individual process.

-

Do children grieve like adults?

Children grieve death and non-death losses just like adults. And like adults, each child’s way of grieving is unique. A child’s grief response is influenced by the child’s personality, temperament, and developmental level. Emotional openness and responsiveness in the home also play a part in a child’s ability to express and experience grief.

Unlike adults, children tend to grieve in spurts and can sometimes appear to be “over” the loss. However, some losses may be re-grieved during successive stage of development, An example is the loss of one’s mother in childhood - sons and daughters may re-grieve the loss when they graduate, marry, become parents, or take part in an event/situation that reminds them of their mother’s absence.

What does it look like when children grieve?

Children have many of the same grief experiences as adults. However, it is important to listen for things that are not said as much as things that are said. Children often communicate what they do not have the words to express through behavior. Regressive behaviors are common - such as loss of toileting skills, bed wetting, asking for a bottle or pacifier long after these items have been put away. Other common experiences include headaches, stomach aches, poor grades, decreased concentration, aggression toward self or others, frequent nightmares, feelings of guilt, changes in appetite, and hypervigilance for others’ safety. Adolescents may pull away, spend excessive time alone in their rooms, or engage in risky / self-destructive behaviors.

How can I help my child?

Be direct and authentic in communication. Give information that is accurate and consistent with the child’s level of development.

Walk with them through the grief, without pushing or pulling them along.

Encourage questions and emotional expression.

Be a safe space. Hope Edelman, author of Motherless Daughters, suggests that the most helpful factor in supporting children through their grief is having at least one stable, consistent, and caring adult in their lives.

-

Surviving the Shipwreck

— by G. Snow

“I'm old. What that means is that I've survived (so far) and a lot of people I've known and loved did not. I've lost friends, best friends, acquaintances, co-workers, grandparents, mom, relatives, teachers, mentors, students, neighbors, and a host of other folks. ..here's my two cents.

I wish I could say you get used to people dying. I never did. I don't want to. It tears a hole through me whenever somebody I love dies, no matter the circumstances. But I don't want it to "not matter". I don't want it to be something that just passes. My scars are a testament to the love and the relationship that I had for and with that person.And if the scar is deep, so was the love. So be it. Scars are a testament to life. Scars are a testament that I can love deeply and live deeply and be cut, or even gouged, and that I can heal and continue to live and continue to love. And the scar tissue is stronger than the original flesh ever was. Scars are a testament to life. Scars are only ugly to people who can't see.

As for grief, you'll find it comes in waves. When the ship is first wrecked, you're drowning, with wreckage all around you. Everything floating around you reminds you of the beauty and the magnificence of the ship that was, and is no more. And all you can do is float. You find some piece of the wreckage and you hang on for a while. Maybe it's some physical thing. Maybe it's a happy memory or a photograph. Maybe it's a person who is also floating. For a while, all you can do is float. Stay alive.

In the beginning, the waves are 100 feet tall and crash over you without mercy. They come 10 seconds apart and don't even give you time to catch your breath. All you can do is hang on and float. After a while, maybe weeks, maybe months, you'll find the waves are still 100 feet tall, but they come further apart. When they come, they still crash all over you and wipe you out. But in between, you can breathe, you can function. You never know what's going to trigger the grief. It might be a song, a picture, a street intersection, the smell of a cup of coffee. It can be just about anything...and the wave comes crashing. But in between waves, there is life.

Somewhere down the line, and it's different for everybody, you find that the waves are only 80 feet tall. Or 50 feet tall. And while they still come, they come further apart. You can see them coming. An anniversary, a birthday, or Christmas, or landing at O'Hare. You can see it coming, for the most part, and prepare yourself. And when it washes over you, you know that somehow you will, again, come out the other side. Soaking wet, sputtering, still hanging on to some tiny piece of the wreckage, but you'll come out.

Take it from an old guy. The waves never stop coming, and somehow you don't really want them to. But you learn that you'll survive them. And other waves will come. And you'll survive them too. If you're lucky, you'll have lots of scars from lots of loves. And lots of shipwrecks.

-

Positivity in grief embraces the idea that two things can be true at the same time. It does not deny the one’s reality.

I may have feelings of hopelessness and hopefulness.

Days filled with deep despair and anguish may have moments of gratitude and love.

My life is completely shattered. My dreams for the future just crashed and burned. But that does not mean that my life will never be purposeful and meaningful again.

Unhelpful (toxic) positivity values the appearance of normalcy over authentic experiences and emotions. It denies one’s reality.

Ask yourself, what is really being communicated when we compliment people for putting on a smile after a tragedy or getting back to “normal” quickly.

A widow may graciously accept the compliment that she is strong and doing well. And, this may be a true statement. But people are often more complex. And, there may be a part of her that is crying on the inside, “I feel shattered, terrified and alone. My husband just died!”

Platitudes are often offered as a way of being “helpful" or “positive” - You are young, you will have more children, life is for the living, life never gives us more than we can bear, etc. These types of comments may leave the griever feeling ashamed of his own healthy grief response. If he internalizes these sentiments, he may disconnect from his feelings and even believe that he does not need to or should not grieve.

It’s not easy to be with someone that’s sad and we’re not always sure what to say after a death or significant loss. It may trigger memories of our own losses and feelings about death. Sometimes, we try to mediate our own discomfort and sadness by changing the subject or interjecting something “positive”. I encourage you to be aware of your own feelings and really listen after asking, “How are you doing?” You cannot fix the situation. And, the griever may not feel like talking. But, you have offered the griever the gift of listening with an open heart. And, you never know how this act of kindness will help someone during their darkest hours.